The internet has a funny way of leading you into forgotten corners of the past.

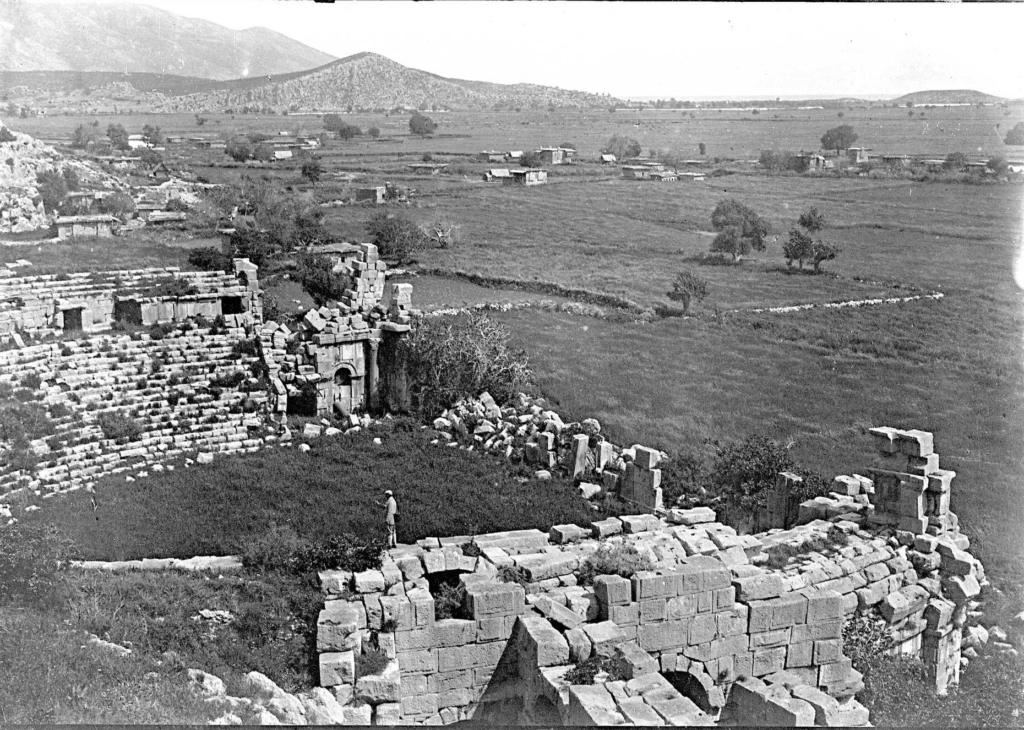

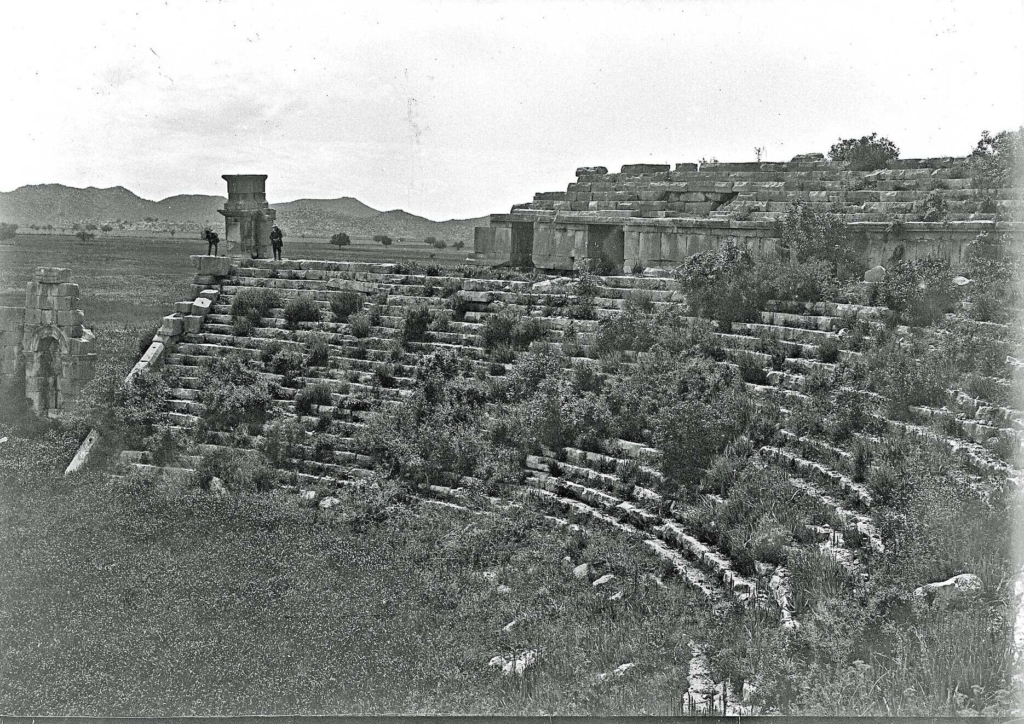

A few evenings ago, while I was doing what I do best—wandering online in search of old stories and hidden images—I stumbled upon two photographs that stopped me in my tracks. They were grainy and quiet, yet powerful. The subject? Myra’s ancient Roman theater, standing in solemn silence long before restoration, long before Demre became the town it is today.

In these black-and-white frames, taken over a century ago, there are no tour groups, no fences, no cafes nearby. Just the curving stone seats of the theater, partially swallowed by grass and time. In the background? The vast Demre plain, with a scattering of tiny houses, wide open farmland, and distant mountains watching over it all. It felt like looking at a time when history hadn’t yet become heritage.

Naturally, I had to know more. After a few determined Google searches, I found what I was looking for: the photographs were taken in 1897 by David George Hogarth, a name I didn’t recognize at first—but one I soon came to appreciate.

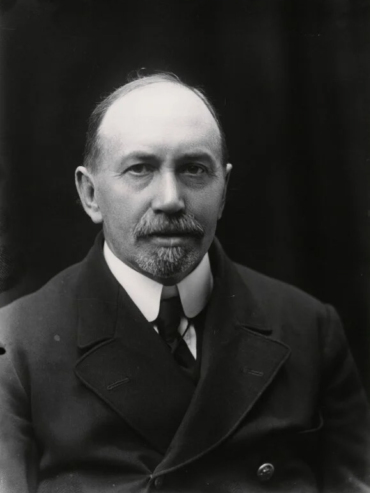

The Man Behind the Lens

David George Hogarth was a British archaeologist, a scholar of the ancient world and one of the key figures in early archaeological exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean. He worked in Egypt, Syria, Cyprus, Crete, and of course, Anatolia. Between 1891 and 1901, he conducted several field expeditions in what was then the Ottoman Empire, documenting ancient ruins with both academic precision and a quiet sense of awe.

Hogarth was not only a field researcher but also played a key role at the British Museum and later became the director of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. His travels through Lycia brought him to Myra, where he took these photos that now feel like time machines.

Demre, Then and Now

What struck me most wasn’t just the image itself—but the realization that Demre has lived side by side with this theater for over 2,000 years. From the time it was built during the Lycian-Roman period, through Byzantine, Seljuk, and Ottoman centuries, and all the way to today—the theater has always been there, watching the town grow, struggle, and transform.

Yet for much of that time, it sat quietly. Locals passed it daily—maybe as children playing among the stones, or farmers tending fields around it. The ruins were familiar, but not always celebrated. They were simply part of the landscape.

Seeing Deeper

Today, visitors come from around the world to see the Myra theater, the Lycian rock tombs, the Church of St. Nicholas, the Andriake harbor, and many other ancient treasures scattered across Demre’s peaceful valleys and coastline. These places are now protected, photographed, and pinned on travel blogs like mine.

But when you walk through them, I hope you’ll think not only of what they once were—but of everyone who lived beside them for centuries without quite realizing the value of what stood in their backyard. Think of the locals, the shepherds, the early explorers like Hogarth, and yes—even the weeds that once covered the marble steps.

Because here in Demre, history isn’t locked behind glass—it’s folded into the land, into daily life, into memory. And sometimes, you don’t need a guidebook to find it. Just an old photograph—and a little curiosity.