Nestled along Turkey’s Mediterranean coast in present-day Demre lies Ancient Myra, one of the most historically significant and visually striking archaeological sites of the Lycian civilization. With its dramatically carved rock tombs adorning sheer cliff faces and a remarkably preserved Roman theater, Myra offers visitors a captivating glimpse into the artistic achievements and cultural practices of ancient Lycia and its subsequent Roman influence.

Dating back to at least the 5th century BCE, Myra rose to prominence as one of the six principal cities of the Lycian League, an early democratic federation. Today, its ruins tell a compelling story of cultural evolution, religious transformation, and artistic mastery spanning nearly two millennia of continuous habitation.

The Lycian Rock-Cut Tombs

Architectural Marvel on the Cliffs

The most visually arresting features of Ancient Myra are undoubtedly its rock-cut tombs carved directly into the steep limestone cliffs that overlook the site. These tombs, grouped into two main necropolises—the River Necropolis and the Ocean Necropolis—represent some of the finest examples of Lycian funerary architecture in all of Anatolia.

Rising in tiers up the vertical rock face, the tombs present an awe-inspiring spectacle. Their distinctive facades meticulously recreate wooden structures, complete with intricate details such as roof beams, ceiling joists, and door panels—essentially translating traditional Lycian wooden architecture into stone permanence. This technique reflects the Lycians’ belief that their tombs should mirror their earthly dwellings, creating eternal houses for the deceased.

Symbolism and Artistic Details

The tombs vary in complexity and ornamentation, reflecting the social status and wealth of their occupants. The most elaborate examples feature:

- Relief Sculptures: Depicting mythological scenes, daily life activities, and funeral processions

- Pilasters and Columns: Often showing Greek influence in their design

- Pediments: Triangular architectural elements above the entrance, sometimes adorned with guardian figures like lions or sphinxes

- False Doors: Symbolic entrances to the afterlife, intricately carved to mimic real wooden doors with panels and hardware

Among the most magnificent is the “Lion Tomb,” named for the imposing lion reliefs that guard its entrance. Another notable example is the “Painted Tomb,” which still retains traces of its original vibrant polychrome decoration—a reminder that these seemingly austere stone facades were once brightly painted in reds, blues, and golds.

Funerary Practices and Beliefs

The Lycian tombs provide valuable insights into ancient funerary customs and spiritual beliefs. The Lycians, unlike many contemporaneous Mediterranean cultures, placed extraordinary emphasis on the construction of elaborate tombs, often investing more resources in these eternal dwellings than in their temples or civic structures.

Inscriptions in the Lycian language (a branch of the Anatolian language family) reveal that many tombs were family sepulchers, passed down through generations. They often contained warnings against unauthorized use or desecration, with the threat of divine retribution for those who violated the sanctity of the tomb.

The elevated position of the tombs—sometimes requiring considerable climbing skill to reach—likely served both practical and symbolic purposes: protection from flooding and tomb raiders, while simultaneously elevating the deceased closer to the heavens.

The Roman Theater

Architectural Design and Features

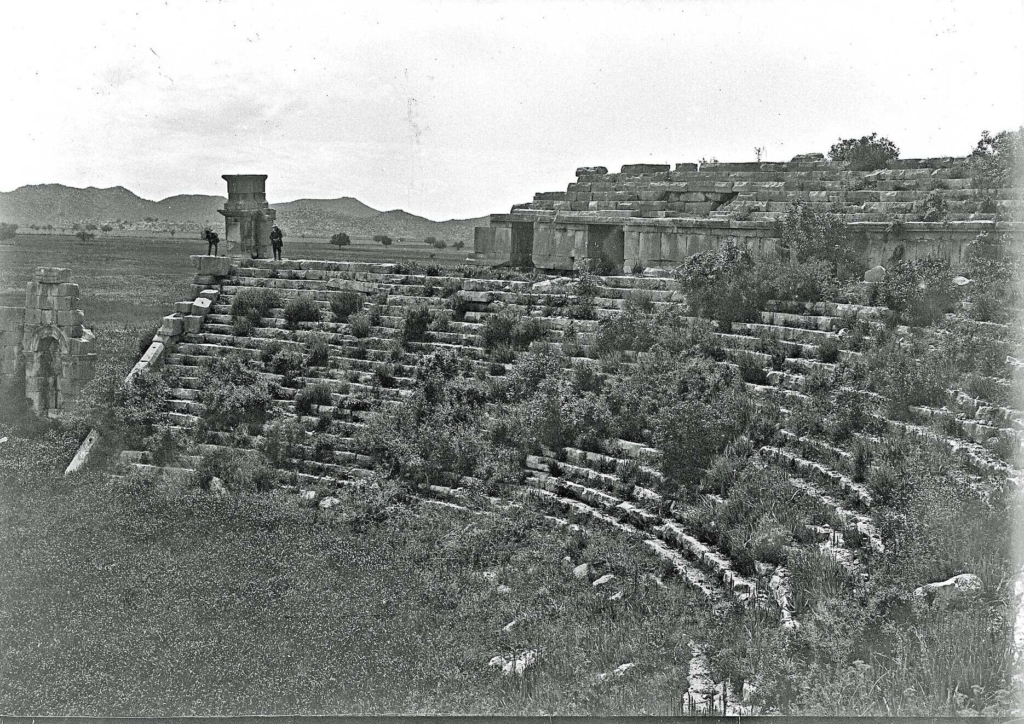

Standing in remarkable preservation at the foot of the cliff is Myra’s grand Roman theater, one of the largest and best-preserved ancient theaters in Anatolia. Built in the 2nd century CE during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the theater could accommodate approximately 11,000-13,000 spectators, testament to Myra’s significance during the Roman Imperial period.

The theater follows the classic Roman semicircular design with key architectural elements including:

- Cavea: The auditorium section with 38 rows of seating divided into upper and lower sections by a diazoma (horizontal walkway)

- Orchestra: The semicircular performance area where the chorus would gather

- Skene: The elaborate three-story stage building, which served as both backdrop and changing area for performers

- Parodos: Vaulted side entrances that gave access to the orchestra

The theater’s remarkable acoustics—still demonstrable today—allowed even whispered lines from the stage to reach the uppermost seats without amplification, showcasing the Romans’ sophisticated understanding of sound dynamics.

Sculptural Decoration

What particularly distinguishes Myra’s theater is its wealth of original sculptural decoration. The stage building’s façade features intricate reliefs depicting scenes from Greek mythology and the cult of Dionysus, the god of theater. Notable among these are:

- Masks representing comedy and tragedy

- Dancing maenads and satyrs (followers of Dionysus)

- Scenes from the life of Dionysus

- Depictions of Apollo and the Muses

Many of these reliefs display high artistic quality and remarkable preservation, offering rare insights into Roman theatrical traditions and religious iconography.

Theatrical Performances and Cultural Life

The theater hosted various performances that formed an integral part of civic and religious life in Roman Myra:

- Tragedies and Comedies: Classical dramatic works by playwrights like Euripides and Aristophanes

- Pantomimes: Popular dance-dramas where masked performers enacted mythological stories

- Rhetorical Contests: Public speaking competitions showcasing oratorical skill

- Gladiatorial Combats: Though less common in eastern theaters, some evidence suggests occasional gladiatorial events

- City Assemblies: The theater also served as a gathering place for political meetings and imperial announcements

Inscriptions found within the theater record benefactions from wealthy citizens who funded performances and structural improvements, highlighting the theater’s role as a focus of civic pride and social competition among Myra’s elite.

Historical Context and Evolution

From Lycian City to Roman Provincial Center

Myra’s development reflects the broader historical currents that shaped Anatolia. Originally a native Lycian settlement with its distinctive culture and language, Myra later absorbed Hellenistic influence following Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BCE. The city was subsequently incorporated into the Roman province of Lycia et Pamphylia in 43 CE.

Under Roman rule, Myra flourished as an administrative center and port city. The emperor Hadrian visited in 131 CE, and his successor Antoninus Pius contributed significantly to the city’s monumental building program. While maintaining its Lycian funerary traditions, the city embraced Roman urban planning, with the theater serving as a powerful symbol of this cultural synthesis.

Byzantine Period and St. Nicholas Connection

Myra’s historical significance continued into the Byzantine era, when it became an important Christian center associated with St. Nicholas, who served as bishop of Myra in the 4th century CE. The Saint’s association with the city—ultimately leading to the modern Santa Claus tradition—brought pilgrims and continued prosperity even as the classical religious practices that had once animated the theater gave way to Christian worship.

Archaeological History and Preservation

The ruins of Myra were first documented by European travelers in the early 19th century, with Charles Fellows’ 1840 expedition producing the first detailed drawings of the rock tombs. Systematic archaeological excavations began in the 20th century, with significant work conducted by Turkish archaeologists from Akdeniz University.

Current preservation efforts focus on:

- Stabilizing the fragile limestone of the rock-cut tombs

- Protecting relief sculptures from weathering and erosion

- Managing increasing tourism to prevent damage to the site

- Documenting the site using advanced technologies like photogrammetry and 3D scanning

Experiencing Ancient Myra Today

Visitors to Myra today can walk among its atmospheric ruins, where the juxtaposition of the soaring rock-cut tombs and the massive theater creates an unforgettable archaeological landscape. The site offers a unique opportunity to experience the layered history of ancient Anatolia, from indigenous Lycian culture to Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine influences.

The best time to visit is during the early morning or late afternoon when the changing light dramatically enhances the carved details of the tombs. Visitors with sufficient time should also explore nearby sites like the Church of St. Nicholas in modern Demre and the ancient harbor of Andriake, which together provide a more complete picture of Myra’s historical significance.

Conclusion

Ancient Myra stands as a testament to the artistic achievement, engineering skill, and cultural sophistication of the civilizations that inhabited this corner of Anatolia. Its rock-cut tombs represent one of the most distinctive expressions of Lycian identity and spiritual beliefs, while its theater exemplifies the grandeur of Roman public architecture.

Together, these monuments offer a tangible connection to the ancient Mediterranean world—a place where indigenous traditions and imported cultural practices merged to create something uniquely beautiful. As modern visitors stand in the theater’s orchestra looking up at the honey-colored tombs, they experience something of what the ancient Myrans themselves might have felt: a profound appreciation for human creativity in the face of mortality, and the enduring power of art to transcend time.